The Challenge

Infectious disease testing is a critical need for humanity. As we struggle with the current COVID-19 pandemic, gaps in our testing technology have contributed to global vulnerability, with devastating outcomes. While our current testing approaches–immunochemistry and nucleic acid detection–are invaluable in the fight against infectious disease, they unfortunately suffer from certain limitations.

Immunochemistry

Rapid and inexpensive, including “antibody” and “antigen” testing, these can often be used without technical expertise. Critically, the usefulness can be limited because their sensitivity is typically low, leading to a high false negative rate. Depending on the assay, distinguishing between current disease states and prior exposure or vaccination can also be a challenge.

In addition, tests for many diseases are unavailable, and development of new diagnostics can be lengthy and uncertain. Further, although antibody detection can sometimes identify the presence of a pathogen, distinguishing between strains or clades and identifying characteristics such as pathogenicity or antibiotic resistance is often not possible.

Nucleic Acid Detection

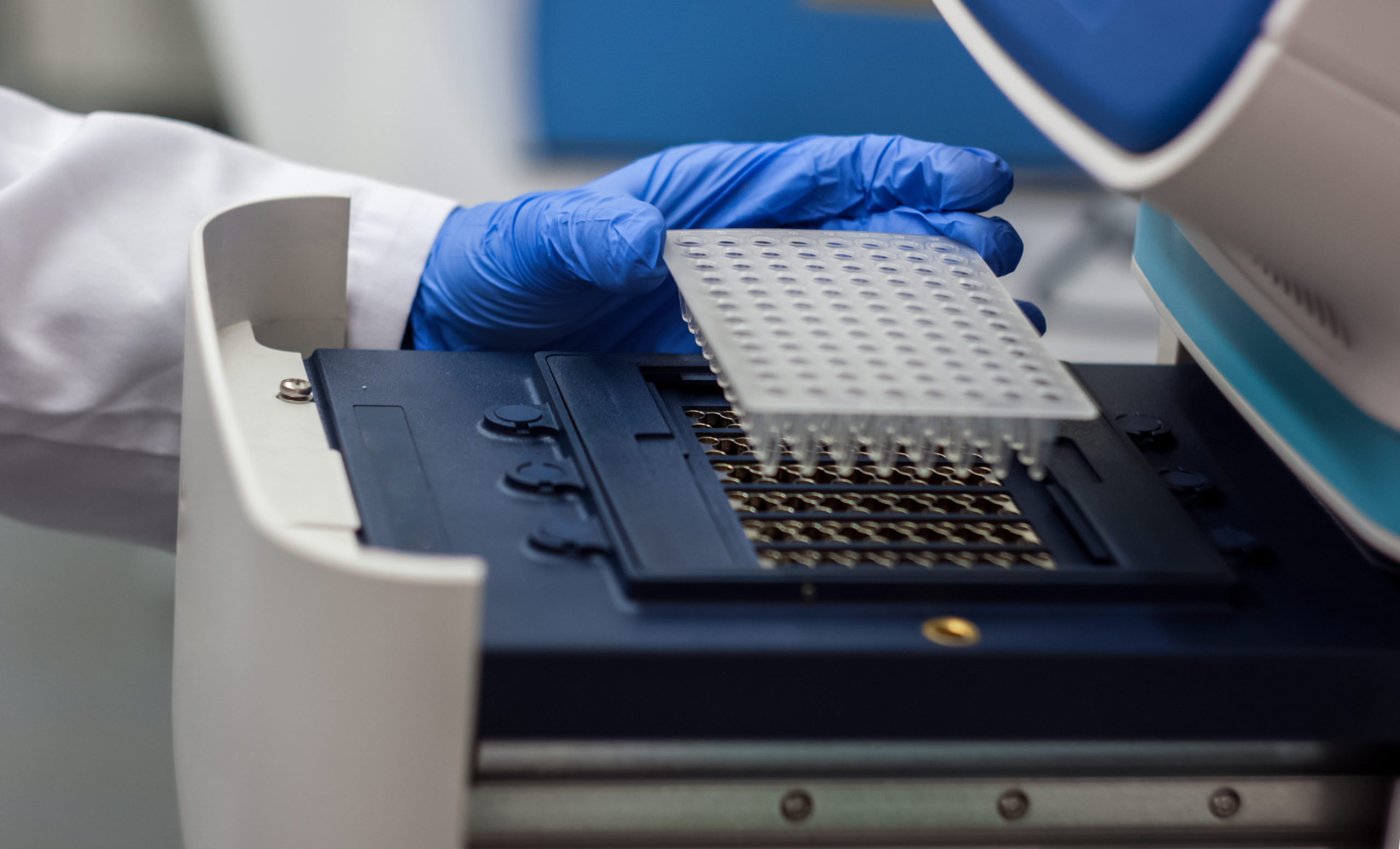

This approach, which includes polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, is highly accurate (meaning highly sensitive and specific, or low rates of false positive and false negative), but typically requires expensive benchtop infrastructure and specially trained technicians to conduct a number of steps, as described on our PCR Testing page. As a result, nucleic acid tests are often relegated to medical facilities where they may not be practically available in a timely fashion where they are needed most. Test results can take days to obtain.

As a result of the above challenges, patients and providers are frequently left with choosing between results that are rapid and inexpensive, but with limited sensitivity, or more accurate results which are slow, and where answers frequently come too late to optimally affect outcomes. Taken together, this results in missed opportunities to more effectively treat infectious disease.

Among other things, the dynamic just described multiplies healthcare costs and slows access at a time when healthcare systems are facing unprecedented social and political pressure.

Diagnostic challenges also add to the unnecessary use of antibiotics, driving the problem of antibiotic resistance, which is estimated to result in millions of deaths annually by 2050.* Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual costs of lost productivity associated with infectious disease were estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars in the U.S. alone.

* Source: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: AMR Report, 2014, Jim O’Neill (Chair)

How is this playing out in the

COVID-19 crisis?

Rapid, inexpensive antibody tests that can be used at the “point of care” (i.e., on-the-spot) have already been developed to help with this crisis. While these are helpful in certain instances, the sensitivity of these tests is often low, especially early in the disease. Releasing a patient into the population after a “false negative” result presents the risk that the patient will continue to spread the virus.

Because of this, PCR tests are needed as they provide results that are much more reliable. Unfortunately, given the dynamic described above, the following challenges exist:

- Sample Collection Issues

- Processing Delays

Sample Collection Issues

The sample collection occurs at the patient’s location, and it requires a specialized “sample collection kit.” Due to the rapid spread of the virus, these kits have been in limited supply, creating an urgent bottleneck in global testing capacity.

Even with the specialized test kit in hand, the patient sample still must typically be collected by healthcare workers in clinics, physician offices or hospitals. In the process, patients often end up congregating; patients who have COVID-19 mix with those who don’t, and the virus has an improved chance to spread.

One potential improvement to the above described process is a drive-through or at-home sample collection approach. Even in these cases, the collected samples, which are potentially an infectious, biohazard material must be carefully transported to the lab, often by mail or courier, which can take days to arrive.

Processing Delays

Outside of medical facilities that have on-site PCR testing capability, trained staff, and the necessary equipment available, PCR testing requires the use of a courier or mail in samples. Once samples arrive at the lab, they are generally run in batches on relatively large, expensive PCR machines by highly trained staff. While the actual PCR test can take less than an hour once everything has been set up, the entire process from sample collection to results typically takes several days or more. During this delay, a potentially infected patient must either self-quarantine, at a substantial personal cost (and possibly unnecessarily if they are healthy) or they may continue to interact with others, creating risk for the community. To make matters worse, test results are sometimes inconclusive, meaning the entire process needs to be repeated.

The timing is inherently so uncertain that, according to a CNBC article on March 14, 2020, even the President of the United States couldn’t escape the delay: “Trump said the test was sent to a lab and he doesn’t know when he will get the results.”

The overall result is that the current testing approach faces challenges addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nuclein can help with this. The Nuclein™ Hand-Held PCR Test is designed to be a disposable, all-in-one, self-test for infectious disease diagnosis. It uses standard, real-time PCR, requires no technical expertise, and delivers battery-powered, sample-to-answer results in under one hour, without the need to mail in a sample. We are working tirelessly to make this available in 2021 to help with the COVID-19 crisis. Please note that this testing device will require FDA regulatory clearance and is meant to be used in consultation with a medical professional.